A deeper consideration of recent policy suggests that a shift might be underway.While the ‘countercyclical policies’ boosted growth, effectively offsetting various economic challenges, they were also riddled with controversy.Slower growth is not necessarily a negative development.

China Policy: From Cyclical To Secular

Global investors have become accustomed to China’s countercyclical policies for more than a decade. Since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, China has adopted large fiscal stimulus and credit boosts to infrastructure and property investments during economic slowdowns – so-called “countercyclical policies” – which have resulted in pronounced investment-driven economic cycles.

And, following a sluggish 2022, a recent policy tone shift from China’s policymakers led many investors to expect a similar, countercyclical stimulus response this year. However, a deeper consideration of recent policy suggests that a shift might be underway. One that changes the focus from quantity of growth to quality of growth – a move that will likely have important implications for China’s economic outlook.

A tale of investment cycles

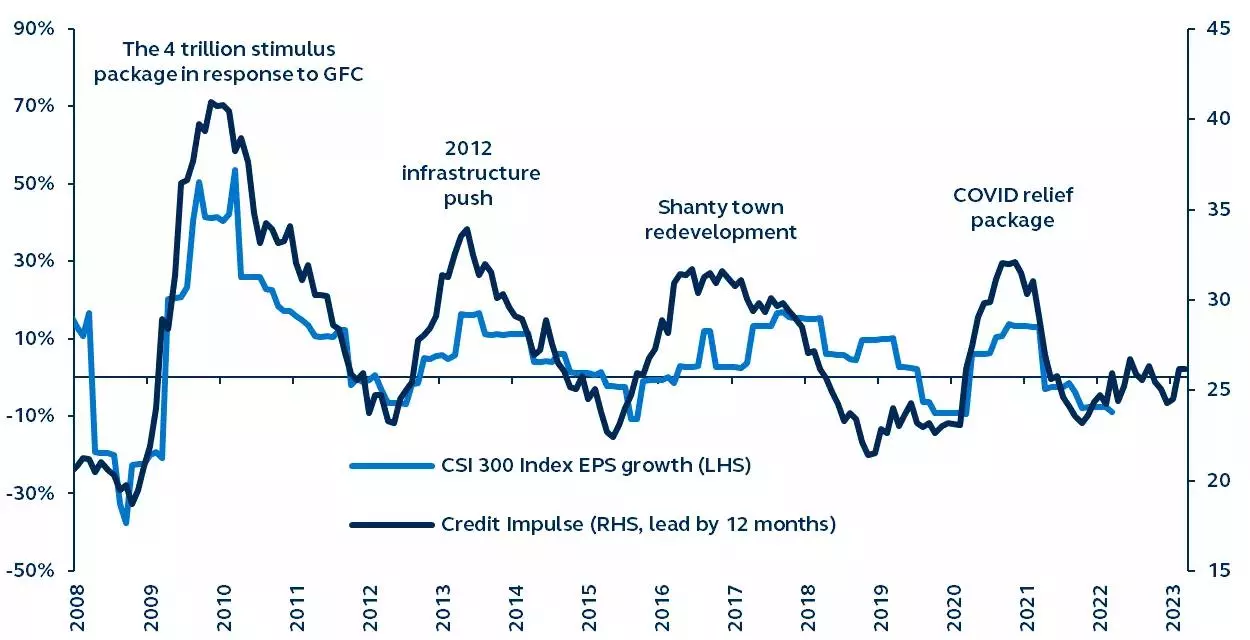

There have been four distinct credit cycles in China during the past 15 years. In 2008, the signature “4 trillion RMB” stimulus package was enacted when the Chinese government strived to fight the export headwinds caused by the severe global recession. That stimulus package was remarkably successful, rejuvenating the Chinese economy and ultimately paving the way for policymakers to follow a similar path whenever the economy showed signs of slowing in the future. In the following years, policymakers introduced a large-scale infrastructure stimulus in 2012, the “shantytown redevelopment projects” in 2015-2017, and the COVID relief package in 2020. These government-funded credit cycles had robust implications on China’s equity market, with earnings growth fluctuating closely in line with the credit impulse, while contributing to large swings in global commodities prices.1

While the “countercyclical policies” boosted growth, effectively offsetting various economic challenges, they were also riddled with controversy. Government-led investment projects resulted in inefficient resource allocation, created bad debt, and bred corruption. The shadow banking challenges during the latter half of the 2010s, as well as the developer debt stresses of 2022, and more recently, the large accumulation of debt in local government funding vehicles (LGFVs), can all cite the credit policies as part of their impetus. Over time, the drawbacks of the large stimulus policies began to outweigh their benefit and the subsequent financial risks that accumulated along the way.

Although policymakers were likely aware of the potential drawbacks of their countercyclical approaches, a wholesale adjustment to China’s massive policy framework was a more treacherous route to follow, particularly given the importance of strong growth to create jobs and drive social stability. As a result, the same credit-heavy path was pursued over the 15-year period, creating significant leverage and imbalances in China’s economy.

China Credit Impulse Index

Level, 2008-present

Note: The China Credit Impulse Index measures the credit cycle in a market. A rising level indicates the economy is recovering. Data as of March 31, 2023.

Shifting to a new policy approach

China’s government has been actively working to adjust its strategy. Indeed, although not widely acknowledged at the time, the Politburo (China’s top decision-making body) meeting in July 2021 was a watershed moment, where policymakers announced “cross-cyclical adjustment” – a strategy that emphasizes preemptive, nimble, targeted, and long-term focused policymaking and avoids excessive and ineffective stimulus. Unlike “countercyclical policies,” which adopt coordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus to counter short-term economic slowdowns, the new policy framework seeks to address long-term structural issues (demographics, technology advancement, financial risks, etc.). Through strategic planning and preemptive policy actions, the aim of the new strategy is to achieve high-quality growth and ensure stability across economic cycles.

At the start of 2022, the new policy framework was immediately tested as COVID lockdowns and restrictive property policies severely hammered China’s economy. Although relief measures did mitigate some of the pain, unlike previous crises, when policymakers had allowed large leverage build-up through government bonds issuance, loan expansion, and shadow banking, the magnitude of the stimulus was relatively small (Read: China’s stimulative policy actions: Turning the tide for investors and China policy stimulus: Muddling through). Moreover, rather than flooding the economy indiscriminately, investors started to see an increasing number of targeted and intentional stimulus measures through central bank relending programs and policy bank-targeted loans. The overall effects are best visualized by the recent movements in China’s credit impulse, which experienced a much lower peak in 2022 than during prior cycles.

China’s aim: A future featuring stability

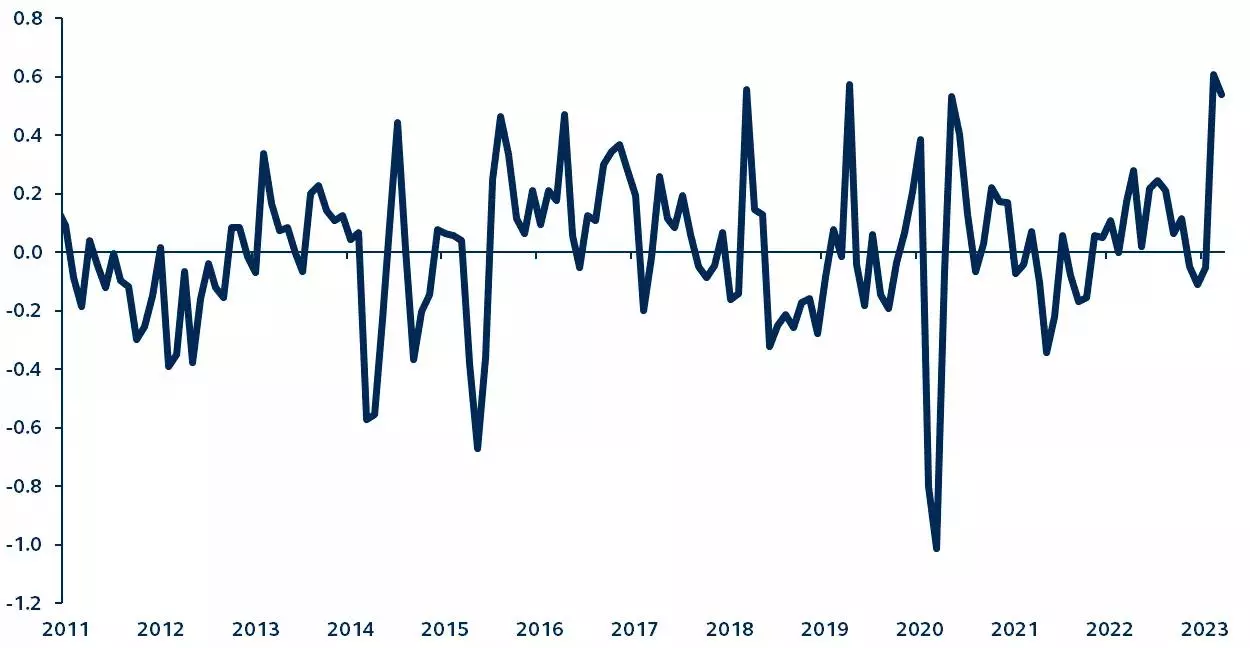

Despite the July 2021 “cross-cyclical adjustment” announcement and subsequent relief measures, investors late last year were hopeful that policymakers would introduce another round of large stimulus, encouraged by an apparent pro-growth policy stance shift at the Central Economic Work Conference and the long overdue unwinding of COVID restrictions. However, the rapid economic recovery since the beginning of 2023 has ultimately reduced the need for additional meaningful stimulus, with economic data beating expectations by the largest margin since April 2020.

Principal Asset Allocation China Economic Surprise Index

Z-score, three-month weighted moving average, 2011-present

Data as of March 31, 2023.

In the “Two Sessions” recently concluded, and in line with the “cross-cyclical adjustment” framework, policymakers provided little reason to expect another credit-inspired boom, which surprised markets to the downside.2

- While China’s robust recovery led some market economists to upgrade their 2023 growth forecast to close to 6.0%, the official GDP target was set to just around 5%, lower than the 5.5% target last year.

- Although China’s announced budget target for 2023 was mostly in line with expectations, additional stimulus was absent.

- China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), has subsequently reiterated the bank’s stance on refraining from excessive credit growth.

The takeaways from the 2023 “Two Sessions” confirm that Chinese policymakers, unlike in years past, are attempting to refrain from overstimulating the economy and that the government has shifted towards a greater focus on quality in its economic planning.

Implications for investors

Unlike many other major economies, the PBoC is still on an easing path. However, any incremental easing will be modest and long-term focused, aiming to avoid unnecessary leverage and risk-taking across the economy.

Global investors may be disappointed, as China’s economic growth is unlikely to revert to the elevated levels seen in the last decade. However, slower growth is not necessarily a negative development. The previous adoption of “countercyclical policies”, which would overwhelm economic slowdowns and provided ample credit for growth, often left the economy veering from sharp upturns to significant slowdowns, rendering the economy reliant on easy money. Now, with the adoption of the “cross-cyclical adjustment” framework, investors should expect that China’s credit growth trajectory will be managed such that it doesn’t lead to boom-bust cycles and excessive leverage. As a result, the country should emerge with a stronger balance sheet and less financial risks.

Investors shouldn’t rule out the revival of a “bazooka” type of stimulus again in the future should an economic slowdown threaten social stability. However, recent history suggests policymakers have so far executed the new framework faithfully and current economic momentum indicates that the requirement for a large stimulus is limited in the short term.

The seemingly prudent and positive policy actions have resulted in a stable outlook for China and made the country a bright spot amid significant global uncertainty around monetary policy and financial stress. Investors, treating China as a key diversifier of global portfolios, should return focus back to organic economic growth and bottom-up fundamentals in China, instead of speculating on large policy stimulus.

1 “Credit impulse” captures the ratio of China’s incremental aggregate financing change to its GDP.

2 China’s “Two-Sessions” are the annual meetings of both the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) that are held independently but at the same time.

Enjoyed this article? Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular insights and stay connected.