Eric Francis/Getty Images News

“Something that everybody knows isn't worth anything.” I wanted to say that Charlie Munger said this, but Bernard Baruch beat him to it.

“Everybody knows that the dice are loaded, Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed,” from “Everybody Knows” by Leonard Cohen, a wise musician.

This article is about Alibaba. It is also about two views of the world by best friends who have seemed joined at the hip for two-thirds of their lives. There are always at least two views on any subject, and the beginning of wisdom lies in understanding that fact. To really understand any subject – take the opposing views of the U.S. and Russia on the Ukraine – it's critical to be able to put yourself in the other guy's place and understand where he is coming from. I remind myself of this fact frequently when thinking about the markets and also in situations involving things like the divergent views my wife and I have about the importance of things like birthdays and holidays. There's a case to be made either way.

(Note: I use the informal Warren and Charlie throughout this article not due to excessive familiarity but fits best because they figure in this discussion as close friends who occasionally differ on a particular subject.)

Warren and Charlie aren't the same person. Warren is the unsurpassed straight man while Charlie's acerbic and perfectly timed ripostes of “No comment” often steal the show. Charlie is much more a big picture guy who looks at the markets in the context of everything that has ever happened on planet earth and elsewhere. To Charlie markets are just a small piece of it. To Warren the markets are everything.

Warren's occasional mistakes often stem from neglecting to context decisions with a broader view or not allowing ideas from different areas to cross-fertilize. Like most of us, his biggest mistakes are actions he didn't take. A key example is his admission that he failed to recognize the future for Amazon (AMZN) and Alphabet (GOOG)(NASDAQ:GOOGL) despite having important information right before his eyes. In the case of Alphabet it was the amount of money Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A)(BRK.B) was spending to advertise on Google. What he learned from that mistake was to tilt his head a few degrees, look at Apple (AAPL) a little differently, and take the plunge.

Warren has often suggested that he depends on Charlie to say no, and at times regrets not listening, but it's likely that at times he needs Charlie to say yes. It is a well known story that it was Charlie who helped Warren escape the pure Ben Graham model of value investing which had worked so well in the years of the Buffett Partnership. Several things were wrong with it. Its premise was to take junky stocks which were dirt cheap because there was something obviously wrong with them and then wring a profit out of unnoticed assets or other reasons they might do better than expected.

The trouble with this as a strategy is that it tends to work just once before it is necessary to exit a position with a profit of 50% or so and find another dog with hidden value. You also have to pay capital gains taxes to your silent partner the IRS. What Charlie suggested, reinforced by Phil Fisher's ground-breaking book Common Stocks And Uncommon Profits, was that turning over a bunch of dogs was too hard (and they were getting scarce anyway). The better way to go was buying great stocks at a fair value over junky stocks that are dirt cheap. The ideal stock has a long growth runway because of some competitive quality which Warren came to describe as a moat. Companies like this can compound money internally for a very long time often without tax consequences. For me, Berkshire Hathaway itself has been exactly the model of such a stock.

So now the question. What's up with Charlie and Alibaba (BABA)? And what's up with Warren and Japan? The funny thing is that neither is what one might expect. You couldn't have predicted what Warren or Charlie was about to do before they did it. Alibaba is a stock with some wonderful operating businesses and a single big problem. I'm a big picture guy like Charlie, and for exactly that reason I have a big reservation about BABA. Every time I read a new SA article about Alibaba pointing out wonderful things involving its growth rate, profit margins, etc, my head automatically forms the sentence “Oh my God, there goes another piece asking and answering the wrong question!'

Bernard Baruch and Leonard Cohen are totally correct about the things that everybody knows. They won't help you. Later I will recapitulate the operating stuff on Alibaba briefly because you need to do that even if you are as sick of hearing it as I am. Everybody knows the quantitative stuff about BABA, and it's great. I freely admit it. Just like Amazon only better, right? What's wrong with it is that you never know whether the Chinese leadership is about to drop the hammer in some awful and unpredictable way. The best minds in the U.S. government can't seem to get their heads around the China problem, and investors have to realize that they can't either. China is the world's most important problem at this particular moment, and it's impossible to calculate the probabilities of what they are going to do on questions that have to do with the fate of the world as we know it.

All I can really do is admit the limitations embodied by my “Oh-MyGod” sentence and acknowledge that the optimists may prove to be right in the end and make a lot of money. If they win big, however, I'm pretty sure it will not be because they correctly calculated the odds. I have never written an article on Alibaba because an honest article on it, by me, would consist of no more than three sentences. In this piece entitled “The China Narrative Is Broken; China Is Uninvestable For Now” on September 1, 2021, I detailed my misgivings in the context of several eras of Chinese history.

The linked article above explained my decision to dump first Alibaba and then the iShares MSCI China Small Cap ETF (ECNS) and avoid all emerging market funds or ETFs with significant China holdings. I didn't KNOW that they were bad investments. What I knew was that there was a large and incalculable risk from the tortuous structure in which BABA and other Chinese companies are packaged for foreign ownership. It was also clear that China no longer needed foreign investors as it had two decades ago and would no longer welcome investments that pulled huge profits out of Chinese enterprises. Charlie Munger could not have been uninformed of these factors. He simply saw the problem differently.

Why Charlie Invested In Alibaba (Probably)

The fact that Charlie Munger had added to his position in Alibaba was a headline revelation and was taken by various writers to conclude that Alibaba's position was fine. Just look at their numbers like Charlie and buy, in this site's most overused phrase, “hand over fist.” To me, that neglected what we mean when we say “risk.” Risk is a concept grounded in the knowledge that more things can happen than do happen. Some of them are quantifiable, like a tendency to earnings misses, and others unquantifiable like nuclear war, although in his 2016 Shareholder Letter Warren took an unusual and creative shot at it:

What’s a small probability in a short period approaches certainty in the longer run. (If there is only one chance in 30 of an event occurring in a given year, the likelihood of it occurring at least once in a century is 96.6%.).”

There are several ironies in Charlie's doubling down on Alibaba. In terms of temperament and the range of things that interest me I probably bear more resemblance to Charlie than to Warren. I like to travel around the world and take a look up close at different people and cultures. The more different from me they are the more they interest me. I like to read about things like ancient history, quantum theory, and how trees evolved into their present forms. None of this has anything to do with investing except that, hey, it's all connected. I believe Charlie thinks that way. I do too.

Did you know that all oak and pine in the 13 colonies standing 24 inches or more in diameter at the base and within three miles of a river (and not within private hands) were reserved for the British Crown? They had a critical need for white pines, the tallest trees in the eastern part of North America, to use as the mainmast of 74-gun ships of the line. You could probably find a pretty good Jeopardy question somewhere in there but I know – and Charlie knows – that one day knowing exactly that fact will make all the difference in our thinking about something or other. So how come our views on BABA are diametrically opposed?

The second irony is that Charlie and Warren seem to have flipped positions when it comes to China and opportunities like Japan. It reminds me of Scott Fitzgerald's final book Tender Is The Night, the book his editor tried to fix after Fitzgerald's death. A young woman with mental health problems and her gifted psychiatrist fall in love and marry. Over time they flip roles as he becomes the one with mental problems and she becomes a movie star. At one point I teased my first wife, a successful artist, that we had experienced a Tender-Is-The-Night transference as she became the driven ambitious one and I became the sensitive one. Half a joke, probably not fair to either of us. Did Warren and Charlie experience a similar transference in their approach to investments?

In this case Alibaba is the deep value play with a single major problem hanging over it which makes the market blind to its virtues. It's a classic Warren Buffet/Ben Graham stock while Warren's Japan is a set of investments to buy and hold as they gradually improve, pay and grow dividends, and compound money. I know, I know, Alibaba is a growth company, not a cigar butt company with a few more puffs in it. Its growth looks uncertain, however, as the government feels free to lay demands on it as a contribution to “Common Prosperity,” the cover slogan that Xi Jinping has applied to buying submission to his authority. Maybe that's fine from the popular political perspective, the Chinese certainly didn't invent the concept, but it makes Alibaba sound a lot like a business used for money laundering by organized crime. Maybe you go home at the end of the day with what's in the cash register and maybe you don't.

So what did Charlie see in BABA?

There's some similarity in the amount of knowledge Charlie and I bring to China. We both probably have more familiarity with China than the average person. His is more immediate in that he has done well over a period of time with Chinese investments helped by his good friend Li Lu of Himalaya Capital. That real world connection is something I don't have. Charlie's successful purchase of BYD, the Chinese electric vehicle company, provided first hand experience with investing in China. It has been a big winner. That has to be part of the context he brings to investing in China.

My knowledge is not so first hand. It stems from taking a few courses from notable professors when I came back to Harvard from Vietnam. I wanted to context my experiences more fully, especially the widely held notion that we were fighting in Vietnam to contain China. All I had learned on that subject in Vietnam was that despite the fact that China had provided the famous Chicom carbines we found in weapons caches or took off of dead Viet Cong, China had historically been Vietnam's mortal enemy. Vietnam's national heroines were the Trung Sisters, often depicted riding an elephant, who led a successful rebellion against Han China at the same time the Roman Emperor Caligula was doing stuff like appointing his horse to the office of consul.

There's a postscript. Thirteen years after I left the Mekong Delta, China and Vietnam fought a one month war at Vietnam's northern border. It didn't surprise me a bit. The domino theory was in serious doubt.

Here's what Charlie saw in Alibaba, the same stuff that everybody interested in the subject already knows:

| ALIBABA | 2016 | 2917 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | TTM |

| Revenues | 15.7 | 23.0 | 30.9 | 56.1 | 72.0 | 109.56 | 126.4 |

| Cost of Revenues | 5.3 | 8.5 | 16.9 | 30.4 | 39.5 | 69.0 | 77.4 |

| Gross Profit | 10.3 | 14.5 | 23.0 | 25.7 | 32.5 | 45.4 | 49.0 |

| Net Income | 11.1 | 6.3 | 10.2 | 17.1 | 21.1 | 22.9 | 19.3 |

| EPS | 4.50 | 2.54 | 3.99 | 5.00 | 8.02 | 8.49 | 7.13 |

| Cash FlowPS | 2.90 | 3.80 | 5.98 | 5.85 | 7.95 | 10.67 | 8.82 |

All numbers are taken from the SA Site with the headings Financials and Cash Flow. The first four rows are in rounded billions, the last two in numbers per share. The 2016 Net Income number is an outlier which includes one-time interest and investment income.

OK, Alibaba is a rapid growth company. The last couple of years show how it has been bloodied by the Chinese government. I read a recent piece saying that being required to donate $15.5 to a Xi Jinping's “Common Prosperity” program is actually good news for BABA. I scratched my head a little about that one. As fast as revenues grow, the cost of revenues numbers have outpaced them. Both gross profit and net income growth trail revenue growth since 2016, and it's not just government actions. So do earnings and cash flow. Another reason that earnings and cash flow grow more slowly than revenues is that the share count increases from share issuance rather than declining from buybacks. BABA doesn't do buybacks. I mean, Alibaba isn't quite Palantir (PLTR) where the share count grows pretty much in lock step with revenues, but it grows enough to ding everything further down on the income statement. None of that is necessarily damning in itself, but the cost and margin numbers over the last few years could have been better.

The Seeking Alpha factor grades are terrible except for an A+ on Profitability and a C on valuation. I have no disagreement with either, although a company with such a growth history should sell for more than a 14.5x. It's too cheap, and that's not necessarily a good thing. The best comparison is to Meta (FB). It has been cheaper than its tech/media peers for a few years, and now everybody knows why. It was cheap in a bad way. I frequently looked at its valuation and wondered if I should buy a few shares but I was saved by the fact that I hated the company, its CEO and founder, and all it stood for with such a passion that it remained on my never touch list. Beware of companies whose CEOs speak only to God, and on a basis of being equals. FB's P/E now is a bit over 18x. That tells us that the market's view is that it is no longer a growth company but a troubled company. It sells at a discount to the market. The same would appear to be the case with BABA.

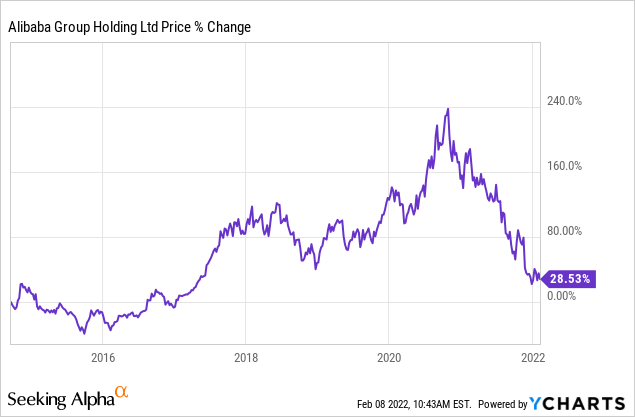

Here's a chart of Alibaba which you can think about for yourselves. It starts with BABA's IPO:

Data by YCharts

What this chart says to me is that investors who bought within the first month after the IPO have made a complete round trip. As of the quote I looked at a few minutes ago they may be up about five bucks per share over more than 7 years. No dividends. No buybacks. No stock splits. Pretty measly shareholder return.

Here's How Charlie Framed The BABA Case (Probably)

The basic value case for anything is grounded in the view that the market has got it wrong and I have got it right. Charlie moved away from that core view half a century ago and pivoted to the idea that the market comes close to getting it right but occasionally misses the quality and durability of growth in the best companies. Examples over the years include Coca-Cola (KO) in the 1980s, many insurance companies, and now Apple (AAPL). I'm assuming that Charlie chipped in with positive confirmation while Warren was buying. The question is whether this thinking about great companies with moats can be massaged in such as a way as to fit Alibaba.

At the May 5, 2018, Berkshire Annual Meeting Charlie said that “Most American investors are missing China.” I'm not so sure about that. At another point, and for the life of me I can't dig it up, he said a few good words about the model of “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” in effect the Chinese model of capitalism. I do think many American investors were not missing China at all as reflected in the fact that between 2000 and 2020 the percentage of China in U.S. cap weighted emerging market indexes went from almost zero (lower than Brazil) to over 40%. The major such indexes are represented in ETFs by Vanguard and BlackRock.

I don't think Chinese investors or other foreign investors alone generated that huge gain in market cap weight. The trouble is that “socialism with Chinese characteristics” dates back to the Third Plenum in 1978 when Deng Xiaoping imposed his liberalizing free market views. The policies of Xi Jinping have been increasingly focused on overturning those views and creating a neo-Maoist China with aggressive foreign policy combined with an assault on many characteristics of Western style capitalism.

For almost four decades American investors grew more and more aware and complacent about the Chinese opportunity. It seemed obvious. All you had to do was sell one donut every week to a quarter of the Chinese population. Do that for a year or two and you can go home a billionaire. The Chinese would even accommodate you by providing the workers and managers. The employees were happy to graduate into the middle class. The population enjoyed eating the donuts. The China narrative was win win win win win win. Pure happiness and bliss. For donuts substitute iPhones, Buicks (for some unknown reason the Chinese like Buicks), or whatever you like.

The second thought always lurking in the back of my mind was how long the Chinese authorities would continue to let foreigners who arrived with an idea and a little cash take that kind of money out of China whenever they felt like it. Sooner or later they would figure out how to make donuts themselves. They would even learn how to create brands and advertise. They would soon do lots of other things without any help. These things all came to pass the same way they did in Japan about three or four years after the end of WWII. I can't help wondering if Charlie, who is absolutely right about the way China bootstrapped from poverty to wealth, may now be out of date when it comes to the basic working principle of contemporary China.

Here's what I believe summarizes the Xi Jinping view of Alibaba. Like Amazon, Alibaba's working model is perfect for rationalizing many sectors of the economy, making them more productive and efficient in providing material goods to the Chinese population. They even employ market forces to calculate demand and arrive at proper and efficient pricing. You can pay its most efficient managers in a way that reflects their efficiency in getting goods to the public at the right price. Meanwhile you can restrict goods and services that attract customers but are harmful to the public good, things like Facebook, maybe, or Bitcoin. I'm definitely with Charlie on those two. We should maybe bring Xi Jinping over here as consultant to get rid of that nonsense, but he's probably too busy. In any case, one day a light switched on in Xi Jinping's head. Maybe it was years ago. Why do we need foreign investors any more, he asked, and what's the point of sending a lot of cash out of the country to people we don't like and are sliding toward a war with?

Moving ever so carefully Xi Jinping brushes aside some basic tenets of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Then, after a trade war and basically failed negotiations on intellectual property rights, he shifts the whole policy into what might more accurately be described as “Stalinism with Chinese characteristics.” A series of small steps changed everything and dropping the hammer on Jack Ma was its coming out moment.

At this moment I have done better on Alibaba than Charlie, the emphasis being on “this moment.” In 2021 he doubled down while I sold. I bought a modest position on March 24, 2020, for $188 per share. It was four days after the absolute pandemic low and I had run out of American things to buy. I sold it in March 2021 for $228 per share, down sharply but still up about 21%. My only regret about Alibaba and the small cap China ETF I owned was that they were supposed to be long term investments and ended up being trades. Otherwise I was happily out of China.

Charlie has to be under water by a fair amount. I acknowledge, of course, that Charlie is ahead of me by many billions lifetime. It's a little like what I told a girl in the early 1990s as Donald Trump walked past our table at a sidewalk restaurant. He was about a foot away yakking loudly about something or other. I told her that he was a big shot but I was richer. I had a net worth of maybe a hundred thousand dollars at that time. His net worth per that morning's Wall Street Journal was negative a quarter of a billion. Plus I had her. I'm likely once again wealthier than Trump for the same reason, but I no longer use it as a sales pitch to a pretty girl. The oblique moral of this story is this: if you're making a decision about Alibaba on anything other than your own rational analysis you should go with Charlie. His long term record speaks for itself. He never yaks, is almost always right, and is ahead of me in net worth by a number I couldn't catch up with if I lived another hundred years.

Why Warren Went With Japan (Probably)

- New Store Stock

- Rivan, Maria (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 208 Pages - 04/14/2020 (Publication Date) -...

- Elevate Your Vision : An Enhanced Vision Board...

- Experience a new level of quality with our...

- Our vision board kit for women offers hand-picked,...

- Whether it’s a gift vision board for teens,...

- At Lamare, our mission is to help women plan and...

- National Geographic Special - 2017-1-20 SIP...

- English (Publication Language)

- 128 Pages - 01/20/2017 (Publication Date) -...

At that same May 2018 Annual Meeting and in answer to the same question which led Charlie to chide American investors about China, Warren said that investing was tough enough in the domestic market without the additional problem that foreign markets presented. If you have to invest billions for it to make a difference it's a nightmare. It's difficult, he said, to invest $8-10 billion so that it matters. He then went on to talk briefly about rule of law and protection of shareholder rights. I should have run immediately to buy Japan.

Things like rule of law and property rights are near the top of every list of investable countries, and they are more than a positive feature. They are an absolute prerequisite. The countries which most closely match up with the U.S. in these essential prerequisites are Israel, Great Britain, and Japan. Buffett has invested in all three and succeeded with two, Israel and Japan. His mistake in Great Britain had to do with a particular company, Tesco (OTCQX:TSCDF), which has eventually straightened itself out after Warren decided that it wasn't worth the trouble and sold at a loss. Japan would currently be my first choice, in part because a number of trends are going in the right direction. It turns out to be Warren's current first choice also. If his next 13F filing, due within a few days, shows that he has doubled his investment in Japanese trading companies, Japan will become his largest ever non-U.S. investment. So what's the attraction with Japan.

On the face of it Japan resembles some of the qualities of the cheap value stocks that Warren bought in his investment partnership sixty years ago. As with China, however, looks may be deceiving. Japan is a growth opportunity, not a huge rapid growth opportunity but growth nonetheless. Among the developed world markets Japan has not been a star in the area of growth since the 1980s. It has in fact been the developed world leader in deflation, stagnation, and below zero interest rates. Starting in 2014, however, all that began to change. The developed world as a whole was too preoccupied with its own problems, while U.S. tech companies were the major game in growth followed by China and Taiwan.

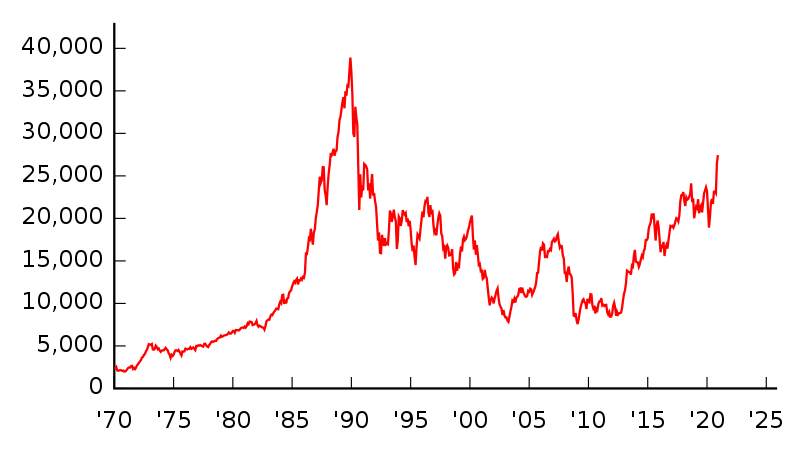

Here's a chart of the Japan market showing the 1989 peak and ensuing crash that exists in the minds of most fairly knowledgable investors:

Wikipedia

That 1989 peak was the end of one era in Japan and the beginning of another. It was also the most overpriced market since tulips. I was relatively poor at the time, making it a good moment to speculate, and I put my entire $20,000 savings after a divorce into a leveraged short using put warrants. It worked well enough that I have never done a speculative thing since. Japan's great post-WWII growth period was officially over. What we have now is a new kind of growth, ignored by the investors everywhere. It is changing Japan fundamentally. The odds are pretty good that after 32 years Japan may soon reach and pass its 1989 high.

In words from my article from September recommending Japan, here's what Warren may have been thinking about it in my words from this earlier article:

It's a great moment for foreign investing. U.S. stocks have become so expensive that an acquisition or major stock position is virtually impossible. The rest of the world is cheaper and offers a wider opportunity.

Japan is the perfect place to start. Japan is one of the world's cheapest markets situated in a stable country with strong rule of law and protection of shareholder interests. While its own markets don't promise outstanding growth (largely due to daunting demographics) it's the gateway to Asia because of its heavy involvement in trade.

Japan is, simply, an adult way to invest in foreign markets, and especially to take a position in both Asia and emerging markets. Political stability, an economy with well established rules, and a strong and long-running alliance with the US make it an ideal core for investment in the Pacific rim.

The trading companies are representative of Japan's basic strengths and core virtues. They participate in other Asian economies through joint ventures and their sophistication about trading and the processing of raw materials into finished goods ties them together with many economies. They are stable, pay good dividends, and are dirt cheap – probably cheaper than any equivalent quality businesses in the world.

Companies which deal in raw materials are well positioned as an inflation hedge. They may be a good way to profit from a rise in commodity prices. Commodities themselves generate no income, but trading companies do.

Japan is a wonderful diversifier and should provide some of the advantages of Markowitz-efficient diversification, producing variance with similar assets in the US. Japan shares many of the virtues of the US economic system, but its economic cycles occur on a different schedule from those of the US or Europe. Its deflationary downturn began a decade earlier than that of the US and Europe, and it felt the impact of difficult demographics earlier than the US.

The whole Japanese market is on sale, and the trading companies are ultra cheap. This is better than buying the dregs and leftovers of an overpriced US market.

Japan's unity is a great asset. Japan has one of the more uniform populations in the world, a contributing factor in its strong cultural identity. These are factors not to be dismissed lightly. Consider the enormous difficulties in the Eurozone which stem from different attitudes toward debt and fiscal responsibility between northern and southern Europe. When striking out for a major foreign commitment, it helps to invest in a country where national cohesion takes these issues off the board.”

Warren Started With The Big Picture (Probably)

They say it's better to buy the worst house in a good neighborhood than the best house in a bad neighborhood. If you notice a great company in Turkey, Brazil, or Argentina I suggest that you first look at the countries and their problems. There is exactly one company from one of these three countries I might buy at the right price, and I'll let you guess in the comments.

What I think impressed Warren at the beginning is how much Japan resembles us in the things that are really important. The Japanese culture makes them quick learners. No two countries ever fought each other quite as savagely as we fought Japan and they fought us, and when it was over both sides had learned to respect and value the other. In the occupation MacArthur rebuilt Japan in our image, and they ran with it so well that for thirty years they were our major economic rival. Warren lived through all that and ultimately noticed the five great trading companies. All of them are conglomerates with some resemblance to Berkshire Hathaway. A light went on.

Meanwhile, enter Shinzo Abe. In his second term as Japan's prime minister, 2012 to 2020 (making him Japan's longest serving leader), Abe enacted the “three arrow” policy (after an ancient Japanese myth) employing (1) liberal monetary policy, (2) liberal fiscal policy with the kind of infrastructure program that President Biden would love to put in place, and (3) a program to deregulate economic zones, include Japan in the Trans Pacific Partnership and negotiate a Japan-EU trade deal, reduce corporate taxes and improve corporate governance, support entrepreneurial business, and push for “a society in which all women can shine.”

The latter arrow was probably the most important, especially the push for companies to include women in leadership positions. The program as a whole amounted to the most powerful reshaping of Japanese businesses and Japanese life since 1946. The short term results are promising and they have already begun to make Japan a more attractive place for foreign investors.

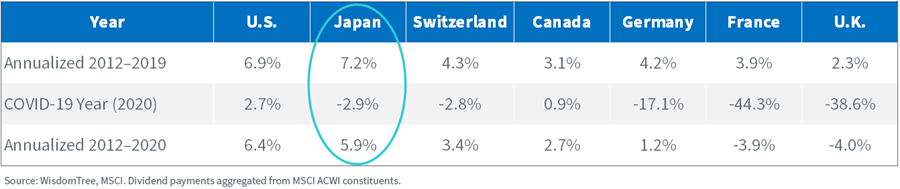

The policies on corporate governance have led to two things American investors can appreciate: rising dividends and share buybacks. It is tempting to see the entire Japanese market as having some resemblance to many American companies with poor prospects for investment or acquisitions in this era of extremely low rates. Instead they manufacture regular per share growth by very substantial buybacks, and the resulting share reduction has made it possible to increase their dividends regularly without seeing more cash go out the door. The chart below, focusing on dividend growth in developed markets, is from WisdomTree, which manages two value oriented Japanese ETFs:

WisdomTree

In the accompanying narrative WisdomTree notes that US investors have not caught up with the story:

Shareholder rights—or lack thereof—has long been an issue with Japan, particularly the far-too-ubiquitous scenario where corporations have piles of cash but pay peanuts in dividends. Year after year, the cash stockpile crushes profitability metrics such as return on equity because the earned interest rate is in the basement…

Suddenly the market finds itself in a scenario where the MSCI Japan index—long notorious for paltry dividends—exceeds the yield of the S&P 500 by 71 basis points (2.03% vs. 1.32%).”

WisdomTree then goes on to cite recent developments stemming from Abe's “third arrow”:

With COVID-19 dominating global headlines, it was easy to miss the update to Japan’s corporate governance code, which happened in June. Notable developments include a new requirement that the number of independent board directors must increase from two individuals to one-third of the mix. Additionally, on board diversity, there is a push to put non-Japanese in senior management, potentially mitigating cronyism. Another initiative that may help Japan’s stock market is a new requirement to publish disclosure materials in English.

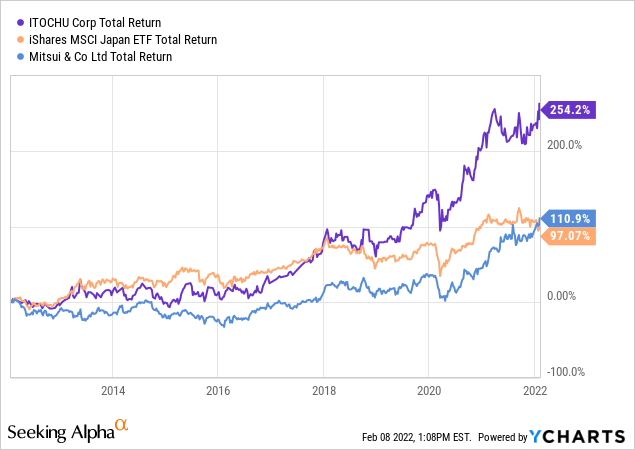

Most foreign investors haven't noticed. Buffett clearly did. But remember, he had likely started with the premise that Japan provided the same stable environment for investors that the United States does. Here's a chart that begins with Abe's return as prime minister and extends to the present:

Data by YCharts

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Baldacci, David (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 487 Pages - 04/16/2024 (Publication Date) - Grand...

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Hannah, Kristin (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 472 Pages - 02/06/2024 (Publication Date) - St....

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Elston, Ashley (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 348 Pages - 01/02/2024 (Publication Date) - Pamela...

Doesn't that look like a bull market? How many people have looked at a chart of Japan in the last ten years? When is the last time you even thought of Japan as a potential investment? Japan is one of the great undercovered investment opportunities and Warren saw it first. In the chart above the iShares Japan ETF (EWJ) is basically the Japanese market. Itochu (OTCPK:ITOCF) and Mitsui (OTCPK:MITSY) are two of the five trading companies Warren bought between August of 2019 and August of 2020. I chose Itochu, bought, and have added. It has done a gangbusters job of developing a value chain which captures the profit of every stage of many consumer products, the imports traveling in their ships, the stores in which they are sold, and their financial subsidiary which enables payment. It sells at a 7.7 PE for an earnings yield around 13%, and it pays a 2.62% dividend. I'm up about 30% from purchase price. Warren has done quite well too.

History Matters: This Is A Tale Of Two Investors, Two Countries, And Three Leaders

Like Warren, I prefer to start with the macro. I bit on the China narrative at almost the peak of its relevance and failed to sell at the absolute top, but one morning I woke up, pulled together the facts that were right before my eyes, and accepted the clear evidence that the China narrative didn't work any more. I sold the same day, profitably, but with disappointment. I had been involved in Japan long (1970s) and short (1989) but Warren's move made me take another look, do some quick study, and buy. I continue to wish the Chinese people well and hope to be able to invest in China again at some point in the future.

The first principles of a country are critical, and the man at the top of any country or enterprise is their key executor. The first leader in this story is Xi Jinping. I could have him all wrong. He may just be devoted to the well being of all Chinese. It's nice to think so. In the meantime his leadership resembles that of all authoritarians, from Stalin back to Caligula. He's not crazy like Caligula, of course, but he clearly believes he rules by something like divine mandate. Stalin, of course, was a nemesis to us but his citizens wept at this death. That includes many of the ones he imprisoned and tortured. Let's leave him out of the list in deference to his people's appreciation of him as a war leader (and maybe ours too).

My second autocratic leader is Mark Zuckerberg who somehow sidled into this article because he fits so perfectly. He has presided over Meta Platforms as a ruler with absolute power because he owns controlling shares. He has no need to listen to anybody. Like Xi, Stalin, and Caligula he is an unlikable individual who may be oblivious to that fact because nobody is there at his side who can tell him. The individuals around him seem to suffer from Stockholm syndrome at least until they escape. He is now in the process of reaping what he has sowed. Autocratic individuals are prone to mistakes that come from not hearing enough points of view.

The third leader, after Xi and Zuckerberg, is of course King George III, the mad British king. You can't exactly say he was unlikable, although he shared some qualities with Caligula, among them a “madness” which made him unable to process important information. He nevertheless got the giant white pine trees he needed until there were no more. The ones he harvested probably remained in service long enough to be the mainmasts of Nelson's fleet although there are stories of his refurbishing some ships after storms or his long chase after the French fleet to the Indies and back. It's still pretty likely tall Maine pines went to battle with Nelson when he destroyed the combined French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar and gave Britain world dominance for a century.

It did not go unnoticed, however, that George III like Xi Jinping intruded on the lives and rights of his subjects. On April 13, 1772, a group of New Hampshire farmers were called in to pay their 50 pound fines for cutting down pine trees with a diameter of 24 inches or more. In Weare, New Hampshire, this led to the somewhat obscure Pine Tree Riot in which the colonials had to be put down by military force and compelled to grudgingly pay their fines. That was that. End of the pine tree story. Then almost exactly three years later a group of “embattled farmers” shot up a bunch of British regulars at Concord Bridge. The rest is history. “Mad King George” went in and out of dubious functionality, was comparatively sane long enough to greet the first American ambassador to his court, rebel leader and future U.S. President John Adams.

The giant white pines eventually began to grow again. It's touch and go for young pine tree sprouts because they need a lot of sun. Only a few make it above the top of rival trees. The odds are not good for a single tree, but with lots of seeds the success of a few is statistically inevitable. You should take a domestic vacation in Maine, eat the local blueberries, have a lobster or three in Bar Harbor, and hike, scramble, or climb in Acadia National Park. Drive around the two states and you'll see that the oldest pines are approaching 3/4 the height of the ones that were cut for British warships. The optimal age for a good mainmast is about 300 years and some of the pines are now well over 200. Once they survive a couple of hundred years they overtop the competition and it's easier to survive the next 100. Ice storms don't bother them much any more than hurricanes at sea did. Most of them make it.