Richard Drury

For two- or three-years central bankers have been exceeding their inflation targets consistently. And yet, central banks are now either executing or considering interest rate cuts for the period ahead. The US, the UK, and the European Monetary Union have been overshooting their inflation targets for nearly three years. Japan has been overshooting its target for about two years. And now without getting inflation back inside the target there are widespread plans some – of them still conditional – for cutting interest rates. The European Central Bank has already executed one cut, but then it stepped back and hasn’t given us a clue as to what it plans to do next or when.

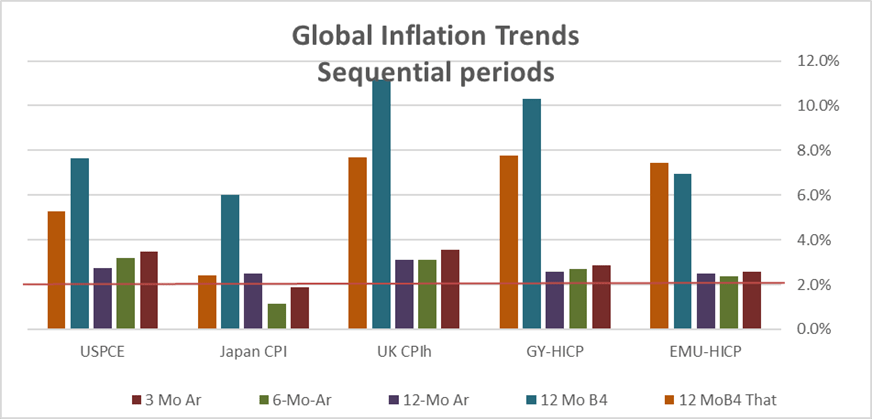

The chart below is illustrative of what’s going on, explaining both why banks think that they’re in a position to reduce rates and also creating some compelling evidence as to why they shouldn’t do it.

global inflation rates (Haver analytics; FAO Economics )

The first 3 bars for each country represent a year-over-year inflation rate, of the past year, the year before that or the year before that. The general pattern (EMU being the only exception) is that inflation jumped up above target for a year, the next year it accelerated further—generally accelerating sharply – and then it decelerated extremely sharply in the third year. It’s this deceleration that has central banks thinking that they have turned the corner on inflation.

However, the last three bars (using the 12-month change bar in both calculations) show us that inflation from 12-months, to six-months, to three-months is generally accelerating and is above target on all those horizons for every country- except for Japan.

Contradictory trends

Central banks remain somewhat mesmerized by their year over year inflation progress and how much inflation has fallen how low its pace is over the last 12 months compares to what they faced over the previous two years. There’s no denying that the progress has been sharp. On the other hand, there’s no denying that central banks have still not attained the target that they have established and that they seek. And so there is tension between these two developments, one that shows a sharp reduction in the inflation rate, the other, that shows ongoing stubbornness and some acceleration for inflation from 12-months to six-months to three-months – amid still excessive inflation.

The farther that we have to look back to find the reassuring trend, the less applicable that trend probably is. The year-over-year comparisons are not as relevant for central bank decisions now even though the results that they portray are stark and encouraging. Instead, it is the creeping inflation from 12-months to six-months to three-months that reveals the most recent trend in play – and a lack of follow-though on falling inflation.

The US experience gone awry

US central bankers in the early days of hiking rates had focused on inflation expectations and argued that they had interest rates high enough because they were above the inflation rate that was expected. However, that really hasn’t worked out. The restrictiveness that Federal Reserve officials thought they were getting from the level of interest rates they implemented simply never materialized. The economy really didn’t slow and while inflation did break lower for a while that stopped and it has since turned to a mild acceleration. As a result of that, the Federal Reserve now talks about being data-dependent, needing to see progress and calling policy ‘restrictive.’

Preempting preemptiveness

When the Fed first talked about monetary policy and what it had to do, it spoke about the need to be preemptive, to cut rates before inflation got down to its 2% mark because it didn’t want to overshoot and drive inflation below the target. However, the reality is that inflation fell very sharply at first, and since then it has stopped falling, flattened, and has started to accelerate slowly. Inflation no longer looks like it’s in any danger of overshooting if the Fed decides to put its foot on the brake a little bit harder to bring inflation to heel.

Theory meets reality

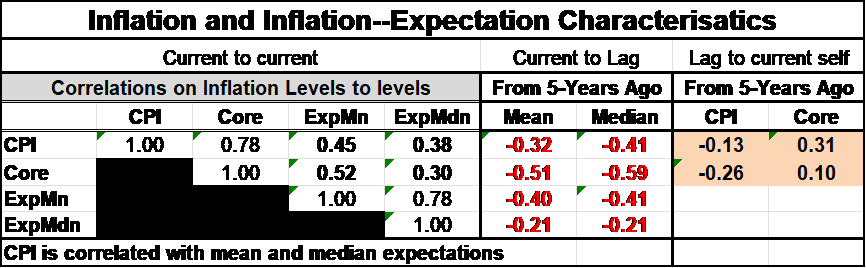

Economic theory focuses on the role of expectations. The Fed argued from the beginning that interest rates are forward-looking statistics- such as the 10-year note, that looks at the interest rate that’s going to pay out over the next 10 years. So, it needed to match that against expected inflation for that period not with trailing inflation. Logically there is no criticism of that approach. It is 100% correct. However, in the table below we present the series of correlations between the CPI in its core and the inflation expectations as measured by the mean and the median of the University of Michigan survey of inflation expectations 5 to 10 years ahead. These statistics are not encouraging from the standpoint of expectations.

Expectations might be the right variable to look at. But, if expectations are poorly formed and if they fail to anticipate the thing that they claim to ‘expect,’ then they’re not going to be very useful and it’s unlikely that anybody is making decisions based upon such expectations. Unfortunately when we vet expectations that is what we find.

The data in the first portion of the table that are labeled ‘current to current’ look at correlations between the year over year CPI, the core CPI, mean expectations, and median expectations. The resulting correlations show modest positive associations between inflation and inflation expectations- these are between current inflation and current expectations being formed for inflation five years in the future. The core of the CPI, and the CPI itself, are correlated at 0.78. The CPI correlates to inflations expectations for the mean and the median at values of 0.45 and 0.38, respectively. The correlation between the core and current expectations that have been formed for five years ahead is about 0.52 for the mean and 0.3 for the median. This shows us that current expectations that are being formed even for five years in the future are positively correlated with what inflation is doing now. Furthermore, we see the correlation between the mean and the median formed at the same time is about 0.78.

expectations (Haver Analytics; FAO Economics)

How do these expectation perform?

The critical question is, “How well do these expectations anticipate the future?” Here, the answer is quite disappointing because the correlations between the mean and the median and both the CPI and the core show negative correlations. (see the section marked current to lag). These are correlations between the mean and the median formed five years ago versus the inflation rate five years in the future. These expectations were set to anticipate future inflation but do a poor job of it. The correlations are negative. They are poor. There’s no reason to think that anyone forming these expectations would be making economic decisions from them.

In the far-right hand panel I calculate the correlations between inflation today and inflation in five years according to different measures (lag to current self). The CPI correlates with CPI and core in the future with the negative correlation. The core is correlated with current CPI and core with low positive correlations.

Let me mention here that if you extract inflation expectations using the gaps between the nominal treasury yields and the treasury inflation protected securities, you’ll get a similar forward-looking inflation expectation that are negatively correlated with future inflation.

These data present a case that undermines the theoretical basis that economists want to use to set monetary policy and that is to use expectations to evaluate the restrictiveness of current interest rates. Now we see why the Fed using that metric to calibrate policy did not work.

A newer, vaguer, policy tact

So, early in this process when the Fed began by talking about interest rates being restrictive comparing them to these different measures of interest rate expectations it became clear that the economy wasn’t behaving as though those were the correct measures. The Fed, more recently, has begun simply talking about interest rates being ‘restrictive’ without telling us what that means… and without explaining whether they thought policy was ‘very’ restrictive or ‘sufficiently’ restrictive. Times change… Not only has the Fed given up thinking it has a precise fix on the real interest rate using expectations, it seems reluctant to even put its characterization in the ball-park.

What sorts of things can we know?

What I have long rejected is the idea that any point forecast of inflation expectations is meaningful. I do believe people have some sense that inflation expectations have risen or fallen and that inflation risks have risen or fallen but I don’t think we can put a precise number on it and that’s a problem for anyone that wants to use statistical analysis to solve this problem. On the other hand, what we do see is that expectations are formed with the significant correlation to what inflation has been. Those are the correlations and the current panel of the table; we know that to some extent inflation expectations are extrapolative. And this is why it in fact has been quite useful to judge monetary policy by looking at interest rates relative to trending inflation because while that doesn’t tell you what inflation is going to be in the future it gives you an idea of the breaking effect. But let’s also realize this is not clear cut. If inflation has been very high and begins to be controlled, it is likely people will be looking for lower inflation in the future not the kind of inflation they have today or had over the past year. But until inflation breaks lower it is unclear how much weight people would place on high inflation falling. Right now even after inflation has broken lower inflation expectations have risen and are moving higher- that is not good news.

The chicken meets the egg

From the standpoint of theoretical economics, all of this is very inconvenient. Theoretically, economics has progressed to point where it’s beyond our ability to use it because the expectations that exist don’t bear much relationship to the future. On the other hand, it’s not surprising because in some ways it’s also illogical to think that markets can forecast inflation in the future without knowing what Fed policy is, and yet the Fed wants to judge the adequacy of its current policy relative to pre-existing inflation expectations, too. How could one exist without the other? We have a simultaneity problem here or something that might be better recognized as a chicken and egg problem.

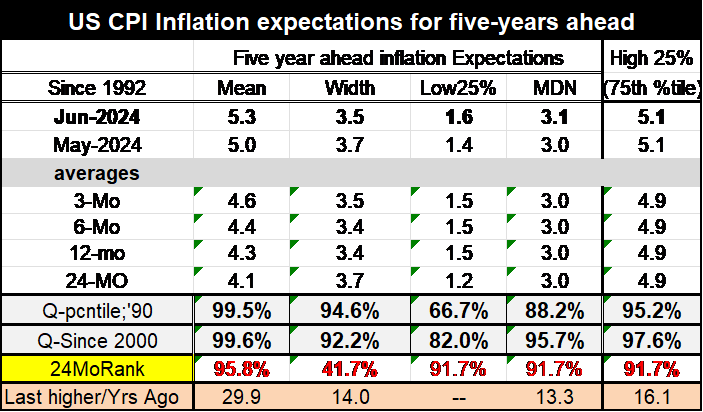

Expectations measures go bananas

I’ve been skeptical of the use of expectations in economics for some time because it seems like something that is either contradictory or based on black magic. What brought these concerns to the fore this week was the release of the University of Michigan’s inflation expectations for the month of June, which currently are on a preliminary basis. The survey showed the median expectation for inflation 5-years ahead rising to 3.1% from 3.0% while the mean expectation rose to 5.3% from 5.0 percent. The mean and the median in this case are really quite different and would have completely different implications for policy, depending on which one you believe. However, what made the Michigan survey pop out this month is the fact that the mean of 5.3% resides at a higher point than the cut off for the highest 25% of the inflation expectations in the survey. That cutoff point occurs at 5.1%. This may seem impossible, however, it’s not, it’s merely improbable. And it has only occurred four times in this series since it’s been released as a continuous monthly series. I’m looking only at the data series for five years ahead. What has happened this month is that the highest inflation for expectations above 5.1% are quite a bit higher than the rest of the survey and they have had an inordinate impact on the mean, driving the mean so high that it resides among the top 25% of forecasts! Yikes!

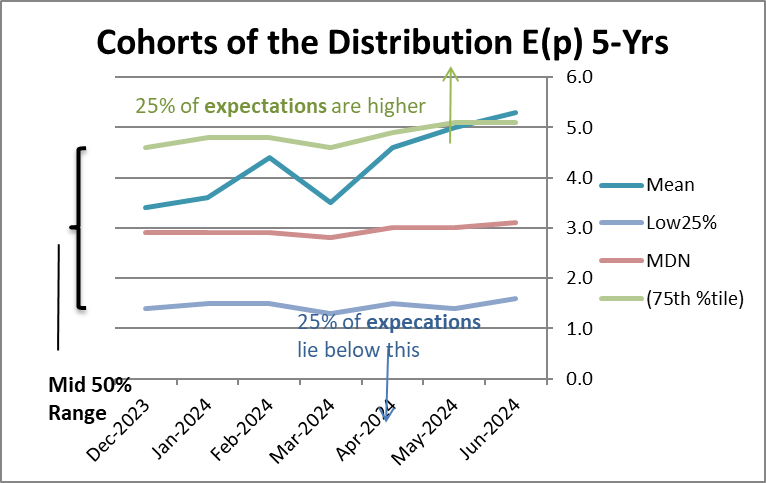

In the chart below, you can see this happening as the mean which is the blue series month-by-month begins to creep higher and higher toward the 75th percentile. The top 75% marker is the dividing line between the top of the middle 50% of the distribution of and the top 25% of expectations. For some time, the mean has been moving up which means that the ‘forecasts’ being made at the high end of the distribution have been getting higher. It’s not a case of there being more high forecasts, since the cutoff is always up to 25% level – the upper 25% tail only has 25% of the forecast in it! The question is what’s the average value of forecasts that are in that top 25 percentile of the distribution since it is open-ended. The answer is whatever that average is, it’s been getting higher and higher and finally, it’s gotten high enough to drive the average for the entire survey above the threshold for the 25-percentile cut off. Wow!!

U of M inflation expectations survey (Haver analytics; FAO Economics)

U of M Inflation boundaries (Haver Analytics; FAO Economics)

And all this statistical mumbo-jumbo means…what?

So, let’s step away from describing the statistics and think a little bit about what this means. I called the Michigan Consumer Survey Center because I wanted to confirm that this unusual result was true; they confirmed it. The next thing they did was try to get me to stop looking at that man behind the curtain! And by that, I mean stop looking at the mean inflation expectation and look more at the median, which they are more impressed with. But here’s the problem with the median… The mean and the median exist among the same distribution of forecasts. These are simply different ways to describe the same distribution. And while the median is always the forecast in the middle and will never rise above the top 75% or below the bottom 25%, that’s by construction. The fact is that what we are really concerned about is what inflation expectations mean. In June the median only rose from 3.0 to 3.1 even though we now have an average for this series that resides above 5.1%. Do we really want to glorify stable expectations for a time series that has this kind of turbulence going on within it? Does 3.1% really characterize the series better than 5.3%?

Guess what 3.1% means?

Next, I calculate rankings for these various metrics. The mean has been higher only 0.4% of the time on data dating back to the year 2000. The median, living in its own more tranquil world, nonetheless has only been higher over that same time span, 4.3% of the time! In relative terms, 3.1% is much higher than it seems! Those standings aren’t so terribly different. The nonparametric view of the median and mean is very similar. And, looked at this way rather than viewing the median as stable we should view it as a relatively high estimate that only seems stable because it varies over such a small range. The median has only been higher 4.3% of the time but because of the compressed way in which it’s reported and acts within this distribution, it has only gone up by 1 tick from 3% to 3.1%. Meanwhile the mean is stretching to the very top of the distribution.

Girth also matters

Another way to think about this problem of expectations is the width of the band that holds 50% of the estimates. We can calculate the width of the band between the low 25% and the high 75% and right now that’s a gap of 3.5 percentage points. On data dating back to 2000, that gap has been wider, less than 8% of the time. This is another statistic that suggests that inflation expectations are not very tightly held. The gap between the highest and lowest estimate at the 25 percentile borders that hold 50% of the observations is unusually wide. So maybe the mean is giving us a better signal after all?

The bottom line

The bottom line to all of this is that it’s clear to me that no matter which of these statistics you look at, if you put them in the proper perspective the mean, the median, the breadth of the distribution, all of it suggests that expectations are not very tightly clustered and, in fact, they’re not anchored. And this further suggests to me that people are concerned about inflation over the period ahead.

Ask Mr central banker!

If people are concerned about the period ahead, why are central banks cutting interest rates with inflation over the top of their targets after going for three years in which inflation has consistently been over the tops of their targets? Increasingly, this becomes a difficult question to answer.

Without providing you with a sufficient answer, I can say with some degree of certainty that central banks have come to place more emphasis on keeping the unemployment rate low and contained. I can’t explain why this has been undertaken as the priority but it appears to have occurred. And, in the US my fear is that one of the factors playing into this is the coming presidential election. I do not like the idea that the Federal Reserve has a policy bias that is going to favor one candidate over the other. I don’t think that a rate cut ahead of the elections would be the critical factor electing Joe Biden, however, it’s something that certainly would favor him more than it would favor Donald Trump. The monetary authority should not be playing this game. It should be making policy based upon the facts and the needs of the economy.

What are the facts… and the needs of the economy?

The more closely we look at the facts and the needs of the economy and the more we look into the future… even though it may be that expectations aren’t well formed about the future… we can see certain risks beginning to well up that are going to need to be dealt with that clearly should be elevating inflation expectations. Against that background, the rise in the mean expectation makes sense to me. The stability of the median expectation makes much less sense to me. We have increasingly unstable geopolitical conditions. The US has committed to support Taiwan. China, having claimed the South China Sea, a claim that is unsupported by the World Court and by all except China’s closest allies, has become more aggressive in asserting its claim. There are various archipelagos in the South China Sea; those territories are much closer to the areas that China claims and that have traditional claims or interests upon these waters. There are now clashes with China there. The flare up in the Middle East demonstrates that conditions there could get much worse. There is an outright war between Ukraine and Russia. Clearly, the transition from Post post-war to Cold War, to a more peaceful transition has ended. Whatever the peace dividend was, it is no more and now America, Europe, Japan—everyone—will be boosting their military budgets. This will put strain on deficits, and this is going to raise the risks of inflation. At the same time there has been less commitment to free trade, and international trade, the US now has some high and long-standing tariffs against China, and it is unclear whether we are going to continue to go farther down the road of protectionism or not. But there’s little in the way of international trade developments that are likely to bring more price discipline and much more that’s likely to bring less price discipline. Inflation risks are rising!

To me, there is no call for central banks to be poised cut interest rates at current levels. Quite apart from the poor past performance and the difficult position of inflation relative to their targets, as well as the current trend of inflation relative to those targets -future risks are rising. The future risks are enough. There are plenty of risk factors to contend with looking ahead. It is frankly hard for me to bring an argument to bear that supports the case for a rate cut anywhere, now.

A counterpoint to central bank policy

So this is my counterpoint to central banks being poised to cut interest rates. The Federal Reserve should not be pointing to the potential for any rate cuts later in the year. The Bank of England, which now seems to have a rate cut queued up for its next meeting at August 1st, similarly is exposed. Central banks need to stick to their knitting and that is controlling inflation and creating financial stability.

Countries have fiscal policy options. They have arms of the government that are dedicated to looking at labor market conditions. It shouldn’t be the central bank’s job to sacrifice inflation progress to avoid an increase in unemployment. We know from the 1970s when policies are made to avoid a central bank’s ‘first duty’ they take us down a very dangerous path and this slope often gets much steeper before leveling out and very often treading that path leads to loss of control and an undesired result.

How to prevent recession: really!

The bottom line is that if central banks want to prevent recession, they need to prevent inflation. When central banks have failed to prevent inflation, it’s foolish to think that they can bring inflation back under control and avoid a recession. The Federal Reserve’s attempt to create a soft landing has created other distortions which currently are racking the housing market in the US and causing U.S. government debt to re-price at higher and higher interest rates increasing in the interest cost of debt. The Fed’s soft landing policy is having not-so-soft consequences. And if it is unable to avoid recession, the consequences of this policy will turn out to be much more painful than anyone can anticipate. That remains a risk.

The real expectations for the future

The economy is currently at risk from both developments, both to too much inflation and to the potential that recession will develop. The unemployment rate in the US has already risen by 0.6 percentage points from its cycle low which has long been viewed on Wall Street as a signal that recession is coming. Since the late 1950s this signal has never failed to signal a recession and this signal has been tripped by every recession. There has been no error from this signal. However, a number of recession signals have been tripped since inflation spiked without a recession developing. Maybe this signal also will prove to be false. But based on the way the economy is developing, I would not want to bet against it. The Fed’s policy choices increasingly paint us into a corner that limits our options. It’s time to prepare for some adverse events. The salad days are done. Whoever is the next president will face some stark choices and no one now seems to be able to think past the elections. Don’t get caught in that trap. We can see what’s coming…

Haver analytics

Enjoyed this article? Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular insights and stay connected.