JPMorgan Chase (NYSE:JPM), Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), and Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) have just executed a deal that, at first glance, seems to be beneficial for all parties involved.

- Goldman is able to divest a $20 billion book of business from its ill-fated foray into consumer finance.

- Apple now has its credit cards serviced by the largest bank in America and one of the most competently run financial services firms in the world.

- JPMorgan is paying less than par value in an unusually pro-buyer deal and also gets to deepen its relationship with one of the largest technology firms in the world.

Goldman’s consumer finance adventurism has been well-documented, and for brevity’s sake, I shan’t recall all the twists and turns here. But, I will say, after taking approximately $7 billion in losses on the consumer side, being able to divest from one of their portfolios for the price of $20 billion represents quite the nice exit for Goldman – dare I say, a coup. The Apple Card portfolio alone has cost Goldman $1 billion of that $7 billion.

After examining some outside numbers and considering the current macroeconomic environment, I think there are some concerns here, primarily for JPMorgan.

The Quality of the Portfolio In Question is… Questionable

As someone who has spent considerable time in both commercial and industrial lending, as well as unsecured business lending, I know the importance of studying cash flows – following the money – and seeing when and how an issuer of debt is able to collect on said debts.

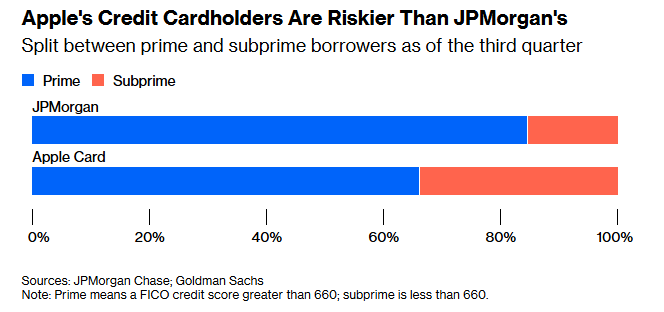

Per the below chart from Bloomberg, this deal represents a portfolio that is substantially riskier than the usual areas JPMorgan likes to play around in. JPMorgan has about 15.5% of its current book under the “subprime” label (FICO < 660), whereas the Apple Card program is more than double that, at 34%.

Bloomberg

Sure, a personal FICO score is far from the only indicator of ability and willingness to repay. And there are some markets where subprime consumers are sometimes more likely to repay than prime. The subprime auto lending market post-Great Recession and pre-pandemic is a historical example of this. These consumers are usually much more likely to rely on their car for daily living and living – in other words, their vehicles are their lifelines. For prime borrowers, cars may not, in fact, be a necessity and are seen as more expendable income, or ancillary.

So, during the aftermath of the Great Recession and pre-pandemic, these borrowers were actually some of the most reliable. Easier lending standards did help more borrowers to qualify, and a better economy provided a boost for these lower-FICO borrowers.

While these trends have not been holding as of late due to rising interest rates and inflation/increasing car prices pressuring lower-income consumers, the point remains that in certain contexts, FICO is not always the definitive, surefire way of determining ability and willingness to repay.

Unfortunately for JPMorgan and Apple, unsecured consumer financing via credit cards is certainly not one of those industries where lower FICO could indicate higher repayment, though.

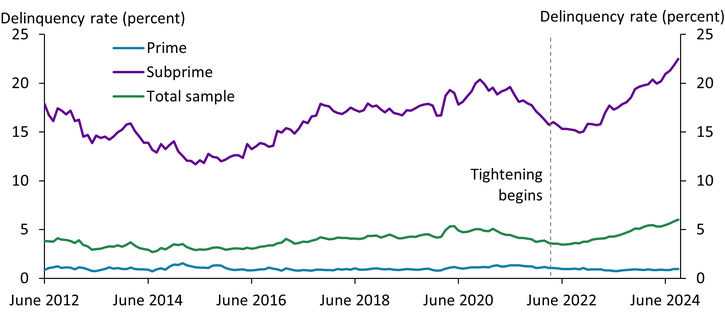

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

(Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City)

While these are not the most up-to-date numbers, this chart is simply illustrative of my broader point – FICO is one of the better indicators for personal unsecured debt repayment – or the lack thereof.

But don’t just take my word for it – reportedly, per the Wall Street Journal back in July 2025, JPMorgan itself had significant reservations about this deal. Even back in 2022, Goldman was reporting significantly higher delinquency rates vs. other subprime lenders on this book of business, hovering at around the 2.93% mark at that time.

What do those loss rates look like now? Unfortunately for JPMorgan, they’re even worse now, at around 4%, and as previously mentioned, the partnership has cost Goldman $1 billion. They haven’t even made money on this – they’ve lost money.

Having this book of business sold at a discount is a highly unusual move. To me, that indicates JPMorgan is not exceedingly confident they will, in fact, be able to collect on a decent portion of these debts. I’m sure this was a big factor in the deal actually happening, with Goldman being the perfect seller, willing to sell at what is essentially the equivalent of a fire sale to get out of Dodge.

Perhaps most of this portfolio’s issues can be attributed to Goldman not exactly being the best servicer. I will give that argument some credence. But for even a well-managed firm like JPMorgan, facts are stubborn things, and the fact is that this book of business they just bought is very likely to be harder to collect on than what they’re used to working with.

From Apple’s point of view, I would be nervous about JPMorgan possibly changing the terms of the credit card product to better reflect current risks. Current card terms are a comparative boon for consumers but, by all accounts, have not been as kind to Goldman. JPMorgan will, from all reports, keep the existing structure in place for existing borrowers. But, for the future, the program may end up getting retooled in a way that is a bit more friendly to them. While this may help with repayment trends, it may also scare off consumers who would have been attracted to the previous terms. This may be what JPMorgan wants, though, as those kinds of consumers are probably more likely to default. But it also risks hurting Apple if, say, the current 3% rewards and no interest on Apple Store purchases were removed. This all remains to be seen.

Conclusion

At first glance, it would appear that the three parties involved have indeed drafted an agreement that would provide benefit to them all. JPMorgan obtains a book of business at a $1 billion discount to its stated par value; Apple gets to deepen a relationship with the largest bank in America and have no interruptions to servicing its credit card clientele; and Goldman Sachs exits an industry it clearly had no business trying to delve into.

However, when examining recent macroeconomic and consumer collection trends, I do have my concerns about how this will continue to unfold. With rising interest rates, the end of an easy money environment, tariffs, and the increasing likelihood of the possibility of war in Taiwan, I think JPMorgan Chase may not see a very good return on its investment.

Would this significantly impact the outlook for JPMorgan? Likely not – remember, this is the largest bank in the United States, and while a complete or near-complete write down of this portfolio would be a big hit for sure, it is functionally a drop in the bucket of its over $4 trillion in assets. (And that scenario of a near total loss is highly unlikely to happen, given even the worst numbers on subprime borrower collection trends.) JPMorgan is simply using a chunk of its $60 billion in excess cash for this deal and is, arguably, as DJ Khaled would famously say, “suffering from success.”

Apple still has a monstrous cash position, as it usually does, despite their cash on hand for the quarter ending September 30, 2025, coming in at $54.7 billion, a 16.07% decline year-over-year. I would argue that Apple currently faces more problems on the continuing innovation and artificial intelligence fronts than anything having to do with its current consumer finance program.

While there may be possible disruptions from a future lack of rare earth metals or potential geopolitical instability, the firm is very adept at sourcing new supplies of cheap labor – a practice that, while quite questionable from an ethical standpoint, has worked well for the company on a financial basis. One issue to keep in mind is that despite their supposedly diversifying away from China, a lot of their investments and new factories in Southeast Asia are in fact owned by Chinese companies. And there is still a huge amount of its supply coming from Taiwanese companies – should there be any conflict between China and Taiwan in the near future, Apple’s operations in the region would likely be heavily impacted.

But those are broader issues, outside the main scope of this article. I think the immediate and longer-term issues that may emerge from the sale of the Apple Card portfolio are more likely to impact JPMorgan’s bottom line, as they are the servicer. Apple will be impacted, to be sure, but to a lesser degree. I think this was mainly a move to help deepen the JPMorgan and Apple relationship, with JPMorgan hoping to cross-sell other financial products and services and Apple hoping to expand its consumer book, too. Unfortunately for JPMorgan, I doubt the types of clients Apple will be bringing in are going to have much capital for the bank to be able to help them with.

Goldman ultimately emerges as the biggest winner from this deal, in my estimation. They’re able to make back a lot of money on a poorly executed consumer finance operation and are able to focus more on servicing the clientele they are most well known for. They’re already going to see a significant one-time bump in earnings per share next quarter from this. Expect this exit to only help Goldman’s bottom line and increase their operational efficiency.

Enjoyed this article? Sign up for our newsletter to receive regular insights and stay connected.